1-2 Musique Brut (Time Records 3008, 1961).

3-11 “Musical experiments” Performed and recorded by Jean Dubuffet january to april 1961.

Expériences Musicales / Musical Experiments

Jean DUBUFFET

PRODUCER’S NOTE

Jean DUBUFFET’S “musical experiments” form a set of 20 pieces, 9 of which have been chosen for this disc.

This selection was made with regard to the “historical” interest of certain works (La fleur de barbe, 1st publicly performed piece – Gai savoir, 1st work using 2 tape recorders – Terre foisonnante, and Prospère, prolifère, his last musical works which were mixed in the recording studio) and with the aim of providing the listener with the widest possible range of the various “instruments” used.

As the different elements which combined to make up these works were recorded using monophonic techniques, they were all produced in mono during DUBUFFET’S lifetime.

They were lucky enough to be able to use the master tapes for Terre foisonnante and Prospère, prolifere, which were mixed in the recording studio; the elements for the final mix were on two distinct tracks and they have decided to keep them separate so that the listener can better appreciate the procedure employed by the composer.

Similarly, they have not tried to artificially “enhance” the sound quality of these recordings (by adding reverberation, for example) as Jean DUBUFFET who was fully aware of his own (and his equipment’s) technical shortcomings, considered the imperfect quality as a random but significant aspect of the end product. Admittedly some of the endings, especially, will appear particularly sudden. To conclude these technical considerations they should point out that one of the tracks in Terre foisonnante fades out before the end; it continues in mono and this is not a sign of a defect in your listening system.

Coucou Bazar – Ce disque a été édité pour accompagner le catalogue de l’exposition Jean Dubuffet, Coucou Bazar au Musée Unterlinden à Colmar du 29 juin au 20 octobre 2002

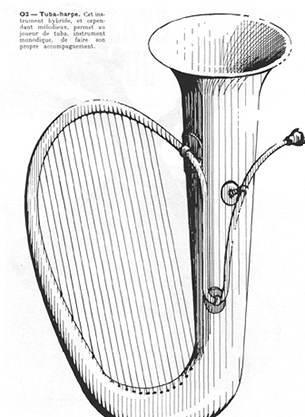

MUSICAL EXPERIMENTS

Towards the end of 1960, around Christmas time, my friend Asger Jorn, the Danish painter, invited me round to improvise music with him. I bought a Grundig TK35 tape recorder to capture the spirit of our get-togethers and the first recording of our recreations, done on 27th December was entitled Nez cassé (Broken nose). Many more were soon to follow as we were both so enthralled by these musical experiments that our improvisation sessions were very frequent over the succeeding months. Asger Jorn had a fair bit of experience with the violin and the trumpet; I had a singular experience of the piano which I had made much use of in former times. However the sort of music we had in mind hardly required virtuoso technique as we intended to use our instruments to obtain unconventional effects. In addition to a pretty bad piano, we started off with a violin, a cello, a trumpet, a recorder a Saharan flute, a guitar and a tambourine. We gradually added all sorts of other instruments, some of them out-dated (old-fashioned flutes, a hurdy gurdy), some exotic (of Asian, African or Tzigane origin), some more common -such as the oboe, saxophone, bassoon, xylophone, zither – and some of folk origin, such as the cabrette and the bombarde – basically, whatever we discovered as we went along. The musician Alain Vian, who has a shop rue Grégoire-de-Tours in Paris selling strange and rare collector’s instruments, was of great assistance; he not only took part once or twice in our little concerts but also managed to find, and sometimes even make, suitable instruments for us.

At the time, neither Asger Jorn nor myself were au fait with the output of contemporary composers and weren’t even familiar with the instigators of serialism, dodecaphony, electronic music and musique concrète. Indeed I only learned these terms recently. My own musical experience was limited to fairly cursory study of classical music on the piano, which I played a lot as a child and teenager and gave up when about 20. Later when I was 35, 1 took up the accordion and its traditional music (with only moderate success) and went back to the piano for a year when I was about 40 to play music by Duke Ellington, interspersed with improvisations on the harmonium. There followed a period when I took a violent dislike to European music and only enjoyed listening to Eastern and Oriental music (I had become fond of the former during my trips to the Sahara).

As for the tape recorder, I was a complete novice. It was only later on that I was to realise that my recordings, done on amateur equipment, left a lot to be desired compared to those carried out by professionals. Strangely enough, however I am not convinced that the latter are really superior. Similarly, I often prefer photographs taken by poorly equipped amateurs than those of specialists. In my subsequent dealings with technicians, I felt that the downside to certain benefits of the care they took in setting-up their equipment, was an inhibiting effect; even if the resulting recordings were very clear and free of flaws and hiccups, they weren’t necessarily any more evocative. I believe that all spheres of the arts could benefit from using simpler techniques. I also believe in getting down to basics, I am all for rugged and unaffected charms rather than frills and furbelows. There is another more important reason for my attitude. We consider that a good recording provides precise and distinct sound which seems to be coming from a close source; in our daily lives, however our hearing is submitted to all sorts of other sounds which, more often than not, are unclear muddled, far from pure, distant and only partially audible. To ignore them is to give birth to a specious artform, exclusively concerned with a single category of sounds which, when it comes down to it, are pretty uncommon in everyday life. I was aiming to produce music based not on a selection of sounds but on sounds that can be heard anywhere on any day and especially those that one hears without really being aware of them. My rudimentary equipment was better suited to this than the most sophisticated machines. Having decided to collect and use whatever kinds of sounds I came across, the sometimes unexpected sounds which in I, tape recorder played back to me were at least as interesting (and sometimes more so) than those I had actually intended to record. When the surprises were in my opinion uninteresting, I rubbed them off, but sometimes they were incredibly good. I transformed a room in my house into a music workshop and in the periods between our get-togethers with Asger Jorn I became a one-man band, playing each of my fifty-odd instruments in turn. Thanks to my tape recorder I was able to play each part successively on the same tape and have the machine play everything back simultaneously. I went about it step by step, recording over the bad sections and using scissors and sticky tape to cut, join and put everything together Such a method entails a lot of trial and error: as it was impossible to hear what I had already recorded when playing a new part, it was very tricky to synchronize them and, struggling to get exactly what I wanted, I had to start over and over again. Nevertheless, the fact that it was so difficult to keep things under control and that I had to trust to luck meant that the risks of failure were offset by the possibility of unexpected surprises. I later added a second tape recorder which enabled me to transfer material from one machine to the other, to play whilst listening to what had already been recorded and to make as many changes as I liked without spoiling the initial recording when the new elements proved disappointing.

The first tape produced in these circumstances is rather unusual as it is a poem, La fleur de barbe, which is declaimed, chanted and vaguely sung by several voices mixed together (which are all in fact mine) with occasional instrumental accompaniment. The subsequent recordings are the result of two diverging approaches which I hesitated between and which are probably both apparent in at least some pieces. The first was an attempt to produce music with, a very human touch, in other words, which expressed people’s moods and their drives as well as the sounds, the general hubbub and the sonorous backdrop of our everyday lives, the noises to which we are so closely connected and, although we don’t realize it, have probably endeared themselves to us and which we would be hard put to do without. There is an osmosis between this permanent music which carries us along and the music we ourselves express; they go together to form the specific music which can be considered as a human beings. Deep down I like to think of this music as music we make, in contrast to another very different music, which greatly stimulates my thoughts and which I call music we listen to. The latter is completely foreign to us and our natural tendencies; it is not human at all and could lead us to hear (or imagine) sounds which would be produced by the elements themselves, independent of human intervention. They would be as strange as what we might hear if we were to put our ear to some opening leading to a world other than our own or if we were to suddenly develop a new form of hearing with which we would become aware of a strange tumult that our senses had been unable to pick up and which might come from elements which were supposedly involved in silent action, such as humus decomposing, grass growing or minerals undergoing transformation. I should point out that in both these categories of music and even when I blend them into one and the same (never mind if this seems illogical), there is a clear preference for very composite sounds which appear to be formed by a great number of voices calling to mind distant murmurs, communities, hustle and bustle and hives of activity. I also have a preference for music without variations, not structured according to a particular system but unchanging, almost formless, as though the pieces had no beginning and no end but were simply extracts taken haphazardly from a ceaseless and ever-flowing score. I must admit that I find this idea very pleasing.

I am, however well aware of the gap between my intentions and the actual results. The experiments which are available in the small collection of records should be considered as outlines for a programme which, if it were to be finalized, would require a lot of improvements such as enhanced recording techniques and better use of each of the instruments. It might also be necessary to modify the instruments or make better adapted ones.

In the meantime, there is still a lot of room for experiment with what is already available. With any instrument one comes across one can get such a great variety of sound effects that it may not be worth looking for others. Instrumental technique and a thorough knowledge of how to get the most from the instruments are clearly sorely lacking; I am very aware that they would be of great use to me.

It might be, however that this would lead to the loss of the benefit of certain unexpected windfalls which can come of improvising on an instrument one doesn’t really know how to use. Having said this, the tracks included on this record were not intended as finished works but as the initial experiments of someone venturing into what is for him, largely unfamiliar territory. I would very much hope that musicians accept to treat them as such.

Jean DUBUFFET, April 1961

Translation by Matthew Daillie